Companies spend considerable time and lose up to $35 million each year trying to get feedback on their leaders’ performance and management behaviors. For some, this is part of identifying management issues, improving employee engagement, minimizing turnover rates, or correcting lackluster productivity. For others, it is a proactive effort to deliver feedback for professional development at all levels. Recently, we have heard from businesses that want to gather more candid feedback from all employees to increase transparency and minimize their leadership bias.

The problem with the current state of upward feedback

The problem is that both organizations and individuals are collecting feedback data in all the wrong ways. Collecting imperfect feedback allows people to make imperfect decisions on bad information, and nothing in the organization changes. The result is missed opportunities for helping remedial and high performers achieve more significant professional growth.

Whether you are an individual hoping to become more self-aware, a leader looking to create a culture of feedback, or an HR executive kicking off upward reviews for the first time, let’s look at how you can put yourself on a path to successful feedback acquisition! Here are some common pitfalls in feedback collection and how they are easily corrected.

The anonymity of those giving upward feedback is in doubt.

Getting honest upward feedback to the top rungs of your organizational ladder almost always requires protecting the identity of the people giving feedback. This anonymity is especially necessary when there are festering cultural issues that leadership is having difficulty tracking down. While it may feel counterintuitive, the direct reports with the most negative feedback are the ones you want to hear feedback from the most. If the folks who give upward feedback fear a backlash in any way, they will hold back their constructive criticism or decline to participate altogether.

If you work in small teams where direct reports have very few other colleagues they work with, getting authentic feedback can be especially challenging as the size of the team can put anonymity in doubt. Additionally, a junior employee in a team of any size is especially prone to doubting the anonymity of these processes. Anonymous surveys are a good place to start, but regardless of how you’re gathering upward feedback, set the boundaries and expectations upfront. Talk to your employees about the difference between confidentiality and anonymity and the limits of both when it comes to ethical or legal concerns within their feedback. The whole team needs to understand how this will impact them.

Collecting upward feedback that is not actionable.

For optimal performance, upward feedback should be actionable feedback. Meaning feedback is given in a way that it’s easily understood and can be acted upon. The best way to ensure this is to use clear, purposeful language and avoid subjective terms such as “I feel” or “I think” when giving upward feedback. Communicate this to those who will give upward feedback through training or other formal communications. Be sure to provide good examples so everyone knows what useful feedback and a valuable tool is.

Additionally, ensure that the feedback you are collecting is helping to answer questions related to performance, progress, or potential. When giving upward feedback, focus on specific behavior with examples, and give actionable advice to help the leader improve in a certain area.

Avoiding tools that allow for easy data analysis.

Collecting upward feedback without the proper tools can lead to inaccurate data and missed opportunities for improvement. Don’t settle for a one-size-fits-all approach with simple survey software, generic forms, and Excel documents. Instead, invest in dedicated tools tailored to specific upward feedback needs. Such tools make it easier to gather relevant upward feedback information from many sources quickly and allow you to analyze the data for patterns that reveal how to move forward.

Employers frequently use a standard performance appraisal method when building out upward feedback programs. This is a classic mistake, but it makes sense. We are conditioned to think about receiving feedback as being connected to our job performance. Instead, a helpful reframe of the upward feedback conversations in your workplace to be focused on relationships, the work environment, and team engagement.

Staying objective in the face of constructive feedback.

While similar to anonymity, objectivity is more about making apples-to-apples comparisons in the upward feedback you get. You want to be careful to define any performance criteria or frame any assessment questions so that people can put aside personal biases to answer them helpfully. That way, you avoid the perspective trap of writing off a long-winded rant as a “disgruntled employee” when there might be some truths beneath the anger that is worth investigating. Sound objectivity in the planning stage also ensures that you have sufficient context for interpreting findings later on — so one person’s performance is viewed accurately within the context of their peer group.

This is a very important part of the upward feedback process. After all, if you get good feedback, but your leaders don’t have the right perspective when absorbing it, none of this really matters.

Inconsistencies in soliciting upward feedback abound.

Speaking of hidden insights, if your data collection is inconsistent or unthoughtful, it will inevitably mess up your findings. You want to ask questions that cover less-obvious topics — a leader’s self-awareness and ability to communicate through conflict, for example — and you want to ask the same questions the same way to everyone. In addition, you only want to investigate topics that you’re prepared to take action on afterward. Otherwise, the message you’re sending to respondents is that you heard their grievances and don’t give a damn.

The analysis of the upward feedback is sloppy.

All too often, the review ends with a small group of people in the organization combing through responses and trying to make sense of them all (usually on top of their other work). Two things are problematic about this approach. The first is that respondents anticipate that this will happen, so they don’t trust and give less-than-honest upward feedback for fear of retribution — see the first bullet point above.

Second, a single person or function lacks the breadth of perspectives needed to understand the data’s implications. The best processes review the data from various angles, including employee engagement and recruitment, business operations, ethics, inclusivity, and legality. This function rarely exists inside an organization with enough distance from the respondents to create validity in the final results.

Delivery of employee feedback is inadequate or non-existent.

Once the whole process has concluded, handling the findings appropriately is crucial. You want to let respondents know they’ve been heard but also what exactly you plan to do to improve or sustain a positive workplace culture — and then do it. You also want to ensure the upward feedback delivery in a useful and usable way. Just sending a report to people without instruction on what it means or what they should do with it is not only unhelpful, it can reinforce many of the trust issues most organizations are trying to avoid in the first place.

By avoiding these mistakes, you will ensure that the upward feedback your organization collects is actionable and accurate so that it can be used to inform better decisions. Investing in the right tools, engaging stakeholders from all levels of the organization, and providing anonymity when necessary will create a culture of candid communication — and, ultimately, a better workplace.

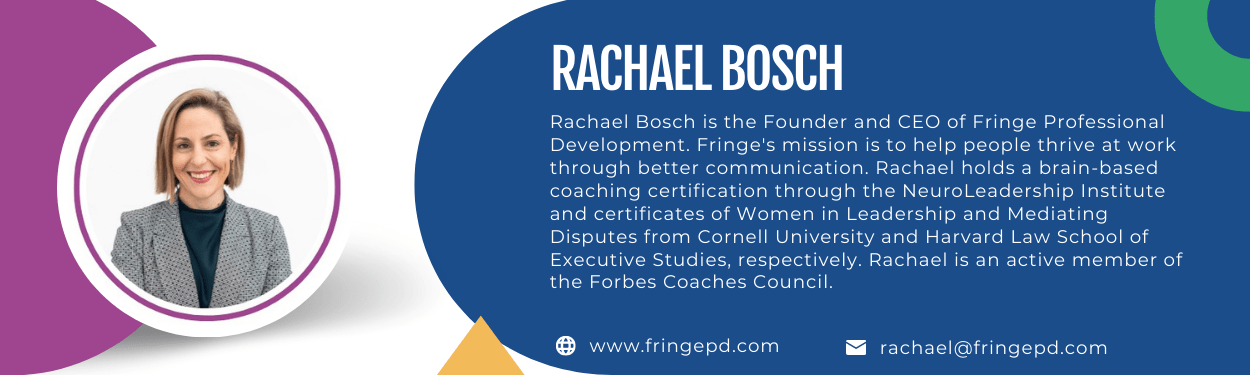

The most successful upward feedback efforts we’ve seen — sparking and sustaining real culture change — involve thoughtful and methodical planning and implementation. At Fringe PD, we are committed to using what we know about the psychology of effective communication and leadership to support companies in this journey.

To learn more about our approach and our tools, visit Fringe PD Assessments, or set up a time to chat!